|

| John McCrae Memorial

"book" close-up. McCrae House,

(Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike 3.0 Unported License)

|

ESSEX FARM CEMETERY, YPRES,

BELGIUM — November

11, 2018 marked the 100th anniversary of the World War I armistice. In many

ways, the "Great War", as it is called, is also the "forgotten

war" because so few Americans know much about it.

In fact,

as of this writing, there is no memorial in our nation's capital that honors those

who perished in the preservation of our

liberty and freedom during World War I.

|

| Muddy trenches were home for four long years (Courtesy: Imperial War Museum) |

In the countries and battlefields where the mayhem took place however, the story is quite different.

In early

May of 1915, Canadian military doctor and artillery commander Major John McCrae

composed his now famous poem In Flanders Fields in tribute to his close friend Lieutenant

Alexis Helmer who was killed on May 2, 1915 in the gun positions near Ypres . Helmer was just 22 years old.

In the

absence of the chaplain who had been called away, McCrae was asked to conduct

the burial of his friend.

It was a

Sunday morning when Helmer left his dugout taking a direct hit from an 8-inch

German shell. He was killed instantly. According to reports "what body

parts could be found were later gathered into sandbags and laid in an army

blanket for burial that evening."

|

| Death march (Courtesy: Imperial War Museum) |

The

memorial ceremony was simple and brief as Major McCrae recited from memory a

few passages from the Church of England's Order of Burial of the Dead. Helmer's

burial site was marked by a simple wooden cross; a grave that has since been

lost.

|

| Essex Farm Cemetery is home to the John McCrae Memorial (Courtesy: Commonwealth War Graves Commission) |

Today,

the John McCrae Memorial Site is a prominent feature of Essex Farm Cemetery

Established

next to a dressing station by the Canadian Field Artillery during the Second

Battle of Ypres, the cemetery is called "Essex Farm" to commemorate

the Essex Regiment. Many believe the name was chosen in honor of a member of

that regiment who was buried there in June 1915.

|

| Model of battlefield and bunkers in Flanders (Courtesy: In Flanders Fields Museum) |

Following

Helmer's burial, it is believed that McCrae began to draft his poem, though

there are several accounts of what happened.

One

version says McCrae was seen writing the poem the next day, sitting on the rear

step of an ambulance while looking at Helmer's grave with the vivid red poppies

that were springing up amongst the graves in the burial ground.

Another

said that McCrae was so upset after Helmer's burial that he wrote the poem in

twenty minutes in an attempt to compose himself.

A third

version by commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Morrison, stated that John drafted

the poem partly to pass the time between the arrival of two groups of wounded soldiers

at the first aid post and partly to experiment with different variations of the

poem's meter.

|

| Trenches, Ypres Salient (Photo: Taylor) |

Regardless

of which story is true, Major McCrae's poem is a haunting reminder of the

insanity of war. During the 16 day of the Second Battle of Ypres , of

which there were a total of five, one observer wrote this account:

"We saw how they crept out to

bury their dead during lulls in the fighting. So the rows of crosses increased

day after day, until in no time at all it had become quite a sizeable cemetery.

Just as John described it, it was not uncommon early in the morning to hear the

larks singing in the brief silences between the bursts of the shells and the

returning salvos of our own nearby guns.”

In the

autumn of 1914 a small burial ground had been established by the French Army on

a canal bank during the First Battle of Ypres. By May of the following year,

the site contained graves of both French and Canadian casualties becoming known

as Essex Farm British

Military Cemetery

It was

during the battle to defend Allied terrain in the northern Ypres Salient, that the

Germans introduced a deadly, never before used weapon, poison gas.

|

| Plaque denotes the first use of poison gas in warfare (Photo: Taylor) |

Major

McCrae submitted his poem to The Spectator magazine but it was rejected and

returned. It was not published until Punch printed it on December 8, 1915.

In the Punch

version the word "blow" is used in the first line even though McCrae

also wrote the word "grow" in other handwritten rewrites. The poem contains

just 15 lines but they are as powerful and poignant as they are haunting:

|

| Poppy fields of Flanders have become the symbol of the region and the war (Photo: Taylor) |

|

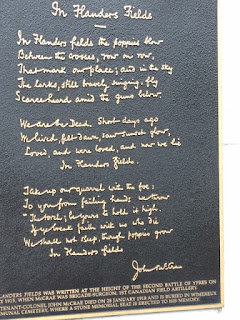

| John McRae's poem (Photo: SherylForbis) |

"In

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields."

Travelers

who visit the Menin Gate Memorial and/or participate in the Last Post ceremony

will find Lieutenant Alex Helmer's name commemorated on Panel 10. His name is

among nearly 55,000 soldiers with no known grave in the battlefields of the

Ypres Salient.

|

| Last Post at Menin Gate in Ypres honors the fallen every night of the year (Courtesy: VisitFlanders.com) |

Today,

in tribute to those fallen warriors, Ypres

honors them with a nightly ceremony known as the "Last Call." A

tradition which has been observed each evening since 1929.